6 Tips to Construct a Productive Study Schedule That Meets Your Needs

Your board exam is coming up. You are probably contemplating mountains of study material and trying not to have a meltdown. Your instinct might be to rely on coffee, cramming, and prayer, and you would not be alone.

Do not trust that instinct.

Multiple cognitive psychology studies2,3,6,7,10,14 show that cramming is not ideal for long-term learning. It may be effective in the short term, but retention decays within days to weeks.9 Given the volume of knowledge required for boards, topics reviewed early on may already be forgotten come exam time.

For enhanced success, you will need time, strategy, and planning to cover it all in a way that sticks, while juggling your clinical duties and the rest of your life.

The following 6 steps should help you create an efficient study schedule that works for you.

1. Choose your learning methods

There is no best way to learn. You might study better alone or in groups depending on the situation. Although everyone has a unique personality, the ideas of “learning styles” or intelligence types are not supported by empirical evidence.11

Available learning media vary widely (e.g., textbooks, blogs, social media, apps, videos, podcasts, lectures, simulations) and employ multiple teaching philosophies and techniques (e.g., mnemonics, algorithms, flash cards, trigger stimulation, cases), each with pros and cons. Choosing ones that suit your preference is okay, but don’t be exclusive. Favor methods that have components of active learning, as these improve retention.5

The must-have weapon in your educational arsenal is repeated testing, also known as retrieval practice, for the following reasons:

- The testing effect is supported by the strongest neuroscientific evidence13 and is superior to repeated reading and concept mapping.8

- The process potentiates long-term retention and improves subsequent retrieval with or without feedback.1

- Getting answers wrong also enhances learning.

- Interim tests promote and sustain the effectiveness of self-directed learning.13

Use the following evidence-based methods with multiple learning techniques to enhance their effect:

- Spaced repetition—has clear superiority to block learning.2,3,6,7

- Repeatedly activated pathways trigger molecular cascades, leading to hardwiring and increased neuron generation.

- Optimal spacing intervals for an exam 1 year away is ~2.5–5 weeks.4

- Spacing with expanding rather than steady intervals improves retention of easy-to-forget material.1

- Interleaving topics, i.e., switching topics up and returning to them—can improve grades independent of spacing.8

- Diversifying learning methods, using varied media and sensory pathways—strengthens connections.5 Try techniques outside your comfort zone.

2. Identify your knowledge gaps

Developing expertise rapidly requires increasing knowledge and organizing it efficiently. Don’t waste time reinforcing your strengths. Identify deficiencies early and continually to guide your study.

The following are good starting points to hunt for knowledge gaps:

- Check the blueprints

- Updated topics and assigned weights are published in exam blueprints, for example, the ABEM blueprint, ABIM blueprint, ABOG QE blueprint, ABOG CE blueprint, ABS QE blueprint, ABS CE blueprint, ABFM blueprint, ABP blueprint, NCCPA blueprint, and ABPN blueprint and model.

- Detailed subtopics can be found in the ABEM Model of Clinical Practice, ABOG Model of Clinical Practice, and ABP Model of Clinical Practice.

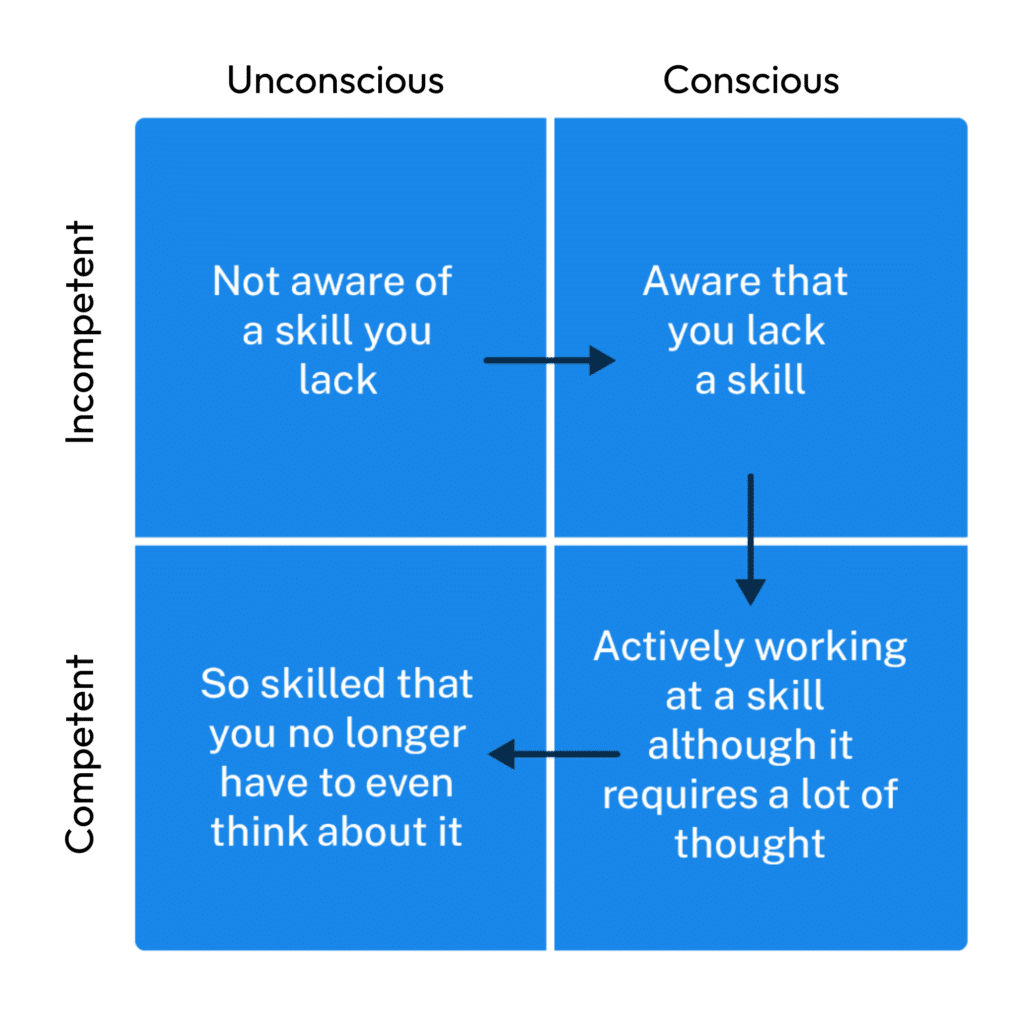

- Check your blind spots

- Avoid unconscious incompetence!

- In-training exams and question banks with objective feedback can be diagnostic. Reflect on mistakes and note your gaps.

- Scan the outlines of review courses or from your study partners for pieces missing from your roadmap.

An efficient way to solidify weak areas is to teach them to others.

3. Define your goals and set deadlines

An effective study schedule should be long, i.e., at least 9–12 months, to cover everything with enough time for spaced repetition and testing. The following can help keep you on track and promote discipline:

- Set clear objectives and deadlines, for example:

- Review all content at least once by halftime

- Complete your third or fourth review by the next quarter

- Reserve your home stretch for testing and practice

- Establish milestones (e.g., cover GI in 2 weeks)

- Set time limits and reminders

- Use an online calendar or study planner

- Track your progress

- Join a study group to harness peer pressure

Maintain motivation by rewarding yourself for attained goals. This positive reinforcement builds stronger neuronal connections.12 Stay motivated by also remembering the big picture: you’re studying to pass exams but also for future practice.

4. Map out your strategy to optimize efficient learning

This is the main course of your study plan. Use the ingredients you selected earlier to create it: high-yield learning methods, recognized knowledge gaps, goals, and deadlines.

An effective strategy I used resembles a spiral path moving inwards, covering material in progressively focused circles as you approach your final goal, with milestones dividing each segment.

First round

Lay out your topics in a logical sequence, prioritized by level of deficiency and assigned weight. I used the following template for each segment:

- Learning phase (2 weeks):

- Chapter summaries, tables, diagrams, and algorithms

- Landmark article appraisals

- Procedural steps and video tutorials

- Testing phase (2 days):

- Practice questions by topic

- Discuss answers, reasoning, and pearls and pitfalls in small groups

- Reflect and plan ahead

Consolidate areas of weakest understanding now, as time for in-depth study will diminish later. Employ previous pro tips: spacing, repetition, diverse media, and teaching others. Remember to cover often-neglected intrinsic competencies, e.g., professionalism, ethics, medicolegal issues, administration, and patient safety.

Subsequent rounds

After the first round, your retention of the topics from the start of the cycle will be weakest.

Don’t panic, this is expected. Remember: repetition, spacing, and interleaving are your friends. Trust that weaknesses become solidified with each pass despite your feeling otherwise.1,7

- Tighten the spiral: refocus attention on persistent deficiencies rather than newly acquired strengths. Each round should be a smaller circle taking less time to complete.

- Try a new medium this time. Remember: revisiting material using different sensory processes enhances retention.5

Stop grouping your test questions by subject and mix them up now. Test yourself with random material. The testing effect works backwards and forwards and enhances learning of old topics even while studying new ones.13

Final stretch

- Pick a quiet setting without distractions or resources.

- Match the number of questions on your test (such as ABEM, ABP, ABIM, ABPN, ABS, ABFM, and NCCPA).

- Disable immediate feedback (i.e., only look at answers at the end).

- Match the time limit (e.g., 3 hours).

Given the question volume, the more you can answer with immediate recall and heuristics, the more time remains for analytic decision-making on the trickier ones.

Reread completed practice tests and correct answers in the days just before the exam. A low-stress, high-yield cram does enhance short-term recall. Make sure to brush up on what to expect on exam day to minimize surprises about rules and logistics, i.e., requirements, forbidden items, time of arrival, duration, etc. (Here’s what to expect on exam day for ABIM, ABFM, ABOG QE, ABOG CE, ABEM, ABP, ABS-CE, ABS-QE, ABPN, and NCCPA.) Lastly, set aside time to visualize and mentally rehearse how to respond to challenges on the exam to strengthen neural connections and improve performance.5

5. Build in rest and self-care

This is a bigger topic, but here’s a quick rundown of activities that affect learning5:

- Helpful:

- Sleeping well

- Eating well

- Exercise

- Moderate stress

- Harmful:

- Fatigue

- Multitasking

- Alcohol

- Excessive stress

Set achievable goals to incorporate into your routine, for example:

- Follow basic sleep hygiene.

- 150 minutes of light exercise or 120 minutes of moderate exercise is recommended weekly. Start low and work your way up.

- Protect study time and space from distractions.

- Try a 3-minute daily mindfulness meditation using an app.

Cash in on banked vacation, personal, or lieu days. Harness your social supports, and blow off steam. One night a month of fun will not lead to failure! It may help you stay the course and avoid burnout.

6. Re-evaluate and adjust

Life is unpredictable. Even without major curveballs during your study period, you’ll likely still have discoveries:

- Unexpected deficiencies

- Novel game-changing literature

- Learning methods that fail

Don’t be afraid to incorporate new strategies. Anticipate making on-the-fly course corrections to weather storms. Flexibility and adaptability in your schedule build resilience to not only become a better test taker, but also a better clinician and life-long learner.

Summary

To recap, these are the steps to making a productive study schedule tailored to your needs:

- Choose effective evidence-based learning methods, i.e., test, space, repeat, and diversify.

- Identify and prioritize your deficiencies, i.e., check blueprints and blind spots.

- Set your goals and structure your time around them.

- Map out your strategy based on the above factors.

- Include mandatory self-care activities.

- Be flexible and continually adjust.

Good luck!

Read up on more of Rosh Review’s study strategies.

References

- Augustin M. How to learn effectively in medical school: test yourself, learn actively, and repeat in intervals. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87(2):207–212.

- Bahrick HP, Bahrick LE, Bahrick AS, Bahrick PE. Maintenance of foreign language vocabulary and the spacing effect. Psychol Sci. 1993;4(5):316–321.

- Bloom KC, Shuell TJ. Effects of massed and distributed practice on the learning and retention of second-language vocabulary. J Educ Res. 1981;74(4):245–248.

- Cepeda NJ, Vul E, Rohrer D, Wixted JT, Pashler H. Spacing effects in learning: a temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(11):1095–1102.

- Friedlander MJ, Andrews L, Armstrong EG, et al. What can medical education learn from the neurobiology of learning? Acad Med. 2011;86(4):415–420.

- Kornell N, Bjork RA. Learning concepts and categories: is spacing the “enemy of induction”? Psychol Sci. 2008;19(6):585–592.

- Kornell N. Optimising learning using flashcards: spacing is more effective than cramming. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2009;23(9):1297–1317.

- Rohrer D, Pashler H. Recent research on human learning challenges conventional instructional strategies.” Educ Res. 2010;39(5):406–412.

- Stahl SM, Davis RL, Kim DH, et al. Play it again: the master psychopharmacology program as an example of interval learning in bite-sized portions. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(8):491–504.

- Vacha EF, McBride MJ. Cramming: a barrier to student success, a way to beat the system or an effective learning strategy? Coll Stud J. 1993;27(1):2–11.

- Waterhouse L. Multiple intelligences, the Mozart effect, and emotional intelligence: a critical review. Educ Psychol. 2006;41(4):207–225.

- Wimmer GE, Li JK, Gorgolewski KJ, Poldrack RA. Reward learning over weeks versus minutes increases the neural representation of value in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2018;38(35):7649–7666.

- Yang C, Potts R, Shanks DR. Enhancing learning and retrieval of new information: a review of the forward testing effect. NPJ Sci Learn. 2018;3(1):8.

- Zechmeister EB, Shaughnessy JJ. When you know that you know and when you think that you know but you don’t. Bull Psychon Soc. 1980;15(1):41–44.

Get Free Access and Join Thousands of Happy Learners

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments (0)