What Doctors Should (But Don’t) Learn About Chronic Diseases in Medical School

On our first day of medical school, the professor put up a slide of a man trying to drink from a fire hydrant. The water represented the amount of information that would be coming at us and the man was a medical student barely able to take in any of it (let alone breathe). The final slide of the lecture stated, “If at first you don’t succeed, you’re about average.”

Despite the quantity of information we would be inundated with, there is a lack of physician training, focus, and specialization in the prevention of chronic diseases (including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.) These diseases burden the health care system with long term-management and the management of acute complications secondary to disease processes.

From the very beginning, I came to understand that “health” was a distinct topic from “medicine.” During a first-year seminar, a bariatric surgeon presented on the various surgical techniques and had a panel of patients for a Q & A session. From the back of the room, I raised my hand and asked, “What could the health care system have done differently to prevent these patients from needing a surgical intervention?” I was assured that it would be covered in other places of the curriculum. But now, with my medical degree in hand, I’m still waiting.

We are undeniably in the midst of a pandemic health crisis. In 2007, a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Obesity and Diabetes in the Developing World — A Growing Challenge” stated that more than 1.1 billion people are overweight, 312 million are obese, 1 billion are hypertensive, and 197 million are diabetic. As a sequela of these chronic conditions, 18 million people die from cardiac disease every year.

In 2014, the annual revenue of the U.S. weight-loss industry was $64 billion. In the past 10 years, the Federal Trade Commission has brought more than 80 law enforcement actions against companies for making false weight-loss claims. Sensa, a weight loss product, was recently fined $26.5 million to settle charges of “deceiving consumers with unfounded weight-loss claims and misleading endorsements.” Weight Watchers, the largest provider of weight loss services in the U.S with 43% market share, sued Jenny Craig in 2010 for making claims that were misleading and not supported by clinical trials. Messages are broadcasted to millions of Americans through social media with bold claims such as “results guaranteed” or “scientific breakthrough.” With more than two-thirds of Americans being overweight or obese and suffering from the complications of these dietary and lifestyle habits, it’s safe to say we have a problem.

Just as pediatricians need to bring up uncomfortable conversations about sex to keep their patients safe and healthy, isn’t it equally the responsibility of physicians to bring up diet and nutrition?

Having personally struggled with weight fluctuations, I found myself emphatically lost and confused as I watched dozens of physicians recommend that their patients try to “eat healthier”—a generic phrase that carries little to no meaning for many of our patients who are already overweight, hypertensive, and diabetic. Other than memorizing the molecular composition of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, my medical education did nothing to prepare me to counsel on nutrition. This is shocking since, according to the Centers for Disease Control, 86% of the nation’s $2.7 trillion annual health care expenditures are spent on chronic diseases that are often both directly and indirectly linked to foods consumed in the Standard American Diet.

While most physicians aren’t trained in nutritional counseling, according to ABC news, celebrities are paid between $500,000 to $3 million to endorse weight-loss programs and are commonly offered an additional average bonus of $33,000 per pound lost. Is that really how we want our patients to get their health information?

Whether as a provider or on the receiving end of care, we have all experienced the rush of primary care physicians who are double-booked every 15 minutes and scrambling to pump out notes for the electronic medical records between patients. With appointment time constraints and unrealistic expectations that a lifestyle change can occur in minutes, we quickly turn to medications to bring down elevated blood pressures, blood sugars, and cholesterol levels—measures that are necessary to prevent coronary artery disease, heart attacks, heart failure, strokes, and the endless complications of diabetes including retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy.

While these drugs temporarily calm our worries of downstream complications, I fear that what we are really doing is superficially masking the symptoms and labs revealing the body’s cry for help. The moment your blood pressure is above 140/90 mm Hg on two consecutive office visits, you’ve earned yourself an antihypertensive medication. If your fasting glucose level is over 100 mg/dL or your hemoglobin A1C is greater than 6%, you’re now prediabetic. Don’t worry, we’ll start you on metformin, which will buy us time until you require exogenous insulin. Our job is to keep you “healthy,” which sadly often translates into following guidelines and algorithms to medicate you properly to bring you back into normal parameters.

It is easier to change a man’s religion than to change his diet.

Margaret Mead, American cultural anthropologist

Food is not only intricately connected to culture and socioeconomic status, but determining the “optimal diet” is a battleground of its own. With so many diverse diets gaining popularity all at once, it’s no surprise that many of us choose to avoid the conversation entirely. After all, who can even keep the trends straight…did they say “high-fat low-carb” or “high-carb low-fat”?

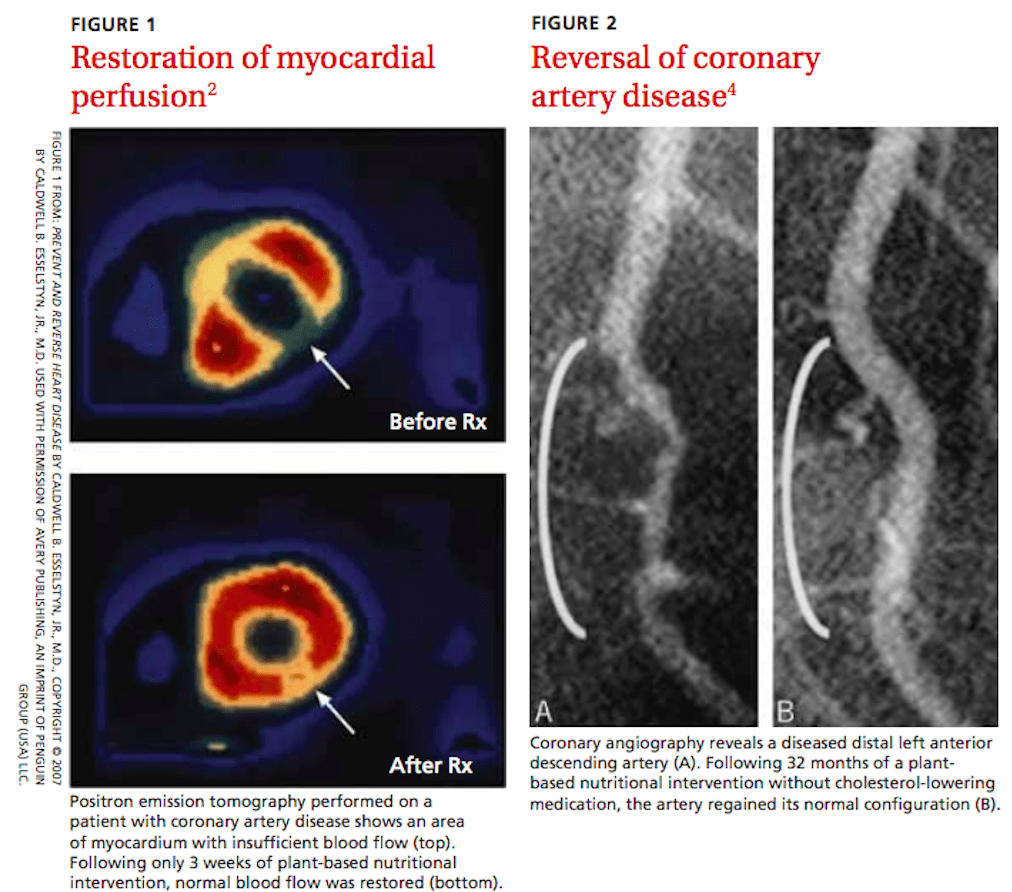

In my search to gain skills on how to counsel my patients about diet, I came across “The China Study,” the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted detailing the connection between nutrition and heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. I wondered why this information wasn’t a part of my medical education, yet I had memorized millions of facts and answered hundreds of thousands of multiple-choice questions about the physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmaceutical treatment of these conditions. The inability to separate disease management from nutrition came across loud and clear in Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn’s research demonstrating that a whole-foods plant-based diet has the ability to not only prevent heart disease but also to reverse it.

Intrigued by the growing movement of physicians who claim they are using whole-food plant-based diets to treat their patients and reverse disease states, I pursued training and certification in Dr. McDougall’s Starch Solution Certification Course. I traveled to Dr. McDougall’s medical practice in California, where I worked with an incredible team to treat patients with food and knowledge. We exchanged the medications used to manage their chronic illnesses with an unlimited buffet of whole-food plant-based meals three times a day (and an overflowing snack room) while providing in-depth education and support to explain how critical these changes were for their health and longevity.

The results I witnessed demonstrated the miraculous power of food as medicine. Over the course of just 10 days, I witnessed one woman’s cholesterol drop by 60 points (greater than what is expected when initiating lipid-lowering therapy with a statin), and one man lost 9 pounds. This program is available as a clinical rotation for medical students and residents. If it sounds like something you would enjoy, I would highly recommend it and would be happy to discuss it further, just shoot me a message!

If reading this gave you an appetite for information to empower yourself with knowledge that you can use and share with your patients, my top recommendation is to start by watching Forks Over Knives, which is available on Netflix or can be rented on youtube for $3.99. It is a worthwhile investment of an hour and a half of your time. If you just want one simple resource, UC Davis has put together a great article on how to read a food label the right way.

While I do not adhere to a one-size-fits-all diet, I believe it’s imperative that we regain our confidence in being competent and capable of speaking with our patients about food and quit being fooled by celebrities and the games of the marketing industry. Fred Flintstone sold Winston Cigarettes until 1970 when Congress passed an act banning the advertisements of cigarettes on television and radio. Fred wasn’t unemployed for long and redirected his persuasive little caveman pitch to children, selling boxes of Fruity Pebbles. Yabba dabba no thank youuuu! We deserve better than that.

Get Free Access and Join Thousands of Happy Learners

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments (0)