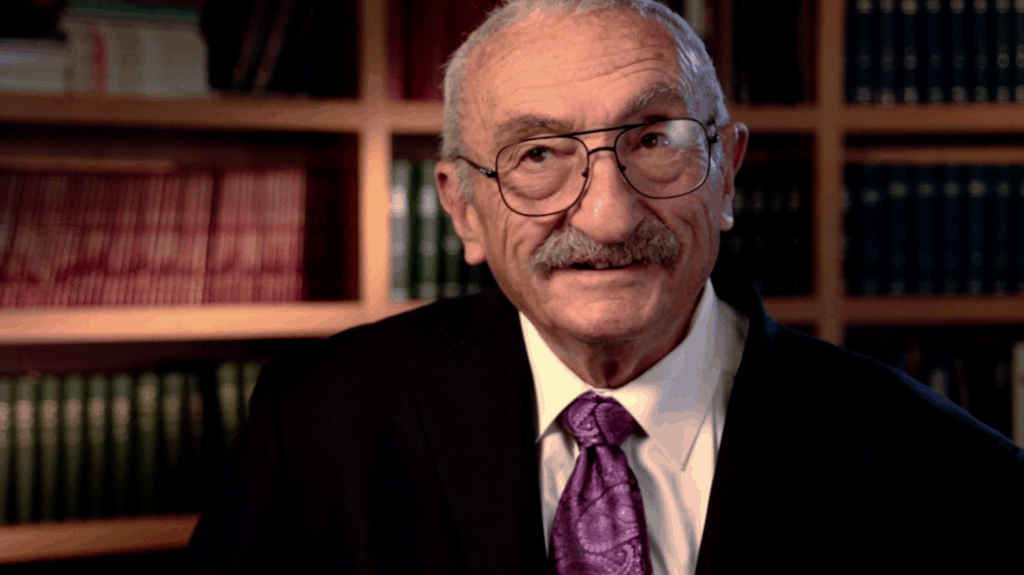

The Interview With Dr. Peter Rosen that Inspired Thousands

Podcast (conversations): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

“Preserve your ideals, don’t let the people around you poke fun at them, and look for where you get your fulfillment and make sure that it is still there and go after it if it is not.”

–Peter Rosen, MD

I think most of you who are emergency physicians know who Peter Rosen is. I mean, let’s face it, back in 2004 when I was a resident, I carried around his 3-volume textbook set everywhere…it was my way to exercise and learn at the same time. I’m just kidding. But I do appreciate that Dr. Rosen decided to merge his textbook into a 2-volume set.

Now…I’ve listened to many other interviews with Peter Rosen and can honestly say this is one you don’t want to miss. We go pretty deep and cover a lot of topics:

- Dr. Rosen’s morning rituals

- His take on physician burnout

- How he maintains a healthy marriage

- Parenting advice

- Who is the most successful person he knows

- What books have shaped him personally and professionally

- How two patients had such an impact on his career that he’ll never forget them

- His regrets

- When are you too old to be practicing emergency medicine

- His views on podcasts

- Open access journals

- Differentiating happiness vs fulfillment

- What he thinks he’ll never get to do in life

- What he wants to be remembered for

- And much, much more

This is Peter Rosen like you’ve never heard him before. So, whether you are a medical student, resident, junior or senior level attending, physician assistant, nurse,…or someone not even in the health professions…there is something for everyone in this episode.

Show Notes:

How to maintain your ideals [5:42]

The second law of thermodynamics and how it applies to life [5:50]

Dr. Rosen’s start as an emergency physician [7:00]

Dr. Rosen’s best published paper [10:15]

PAs and NPs in the emergency department [12:20]

Cardiac care [23:00]

The emergency physician is what I dreamed what the physician was [25:40]

When do you stop practicing emergency medicine? [26:00]

Death is our failure for the emergency physician [28:00]

Acute grief is like being kicked in the testicles [28:35]

Nonsurgical appendectomies influenced by money [31:00]

Rafael Nadal and appendicitis [32:30]

Online, open-access medical education [33:40]

Podcasts [36:10]

5 ways to die [39:15]

Two patients Dr. Rosen will always remember [41:58]

What is Dr. Rosen most proud of [46:20]

Lessons from Dr. Rosen’s father [47:20]

Something people don’t know about Dr. Rosen [50:00]

How reading has impacted Dr. Rosen [50:30]

Favorite books [52:00]

Parenting tips [1:00]

Definition of success [1:05]

Not getting into medical the first time [1:02]

Being remembered [1:05]

Do people have a calling [1:06]

Advice on marriage [1:09]

Morning rituals [1:14]

On burnout [1:30]

Books Mentioned:

The Red and the Black by Stendhal

The Youngest Science: Notes of a Medicine-Watcher by Lewis Thomas

The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher by Lewis Thomas

The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher by Lewis Thomas

The Horse and Buggy Doctor by Arthur Hertzler

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

Cicero: Selected Works by Marcus Tullius Cicero

Podcast (conversations): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Dr. Adam Rosh: Welcome to another episode of Conversations. This is Adam Rosh and I want to thank you for joining me. To kick off the first episode, I thought I’d start with a conversation I had with Dr. Peter Rosen back in 2016. As some of you may know, Dr. Rosen passed away last year in 2019 at the age of 84. His professional life and legacy are truly defined by really decades-long campaign to legitimize emergency medicine as a discipline and a field of study and a vital academic specialty. In these efforts he was largely successful. Since the last 20 years of my life have been defined by emergency medicine, I thought it would be a nice tribute to kick off the Conversations podcast with Dr. Rosen. So this episode was so much more than hearing how Dr. Rosen’s work was integral in helping to develop this specialty of emergency medicine. We get to see a very human side of Dr. Rosen. Again, just so you are aware, the episode will start with the original introduction to the conversation which was recorded on May 2, 2016. I think you’re going to enjoy this. So without further ado, here is my conversation with Dr. Peter Rosen.

I hope everyone is doing great and having a great day. Now today’s episode is very special to me. Let me tell you, you’re in for a real treat. We’re going to be talking with Dr. Peter Rosen. Yes, the Peter Rosen. I think most of you who are emergency physicians know who Peter Rosen is. I mean let’s face it. Back in 2004 when I was a resident, I carried around his three volume textbook set everywhere I went. It was my way to exercise and learn at the same time. Just kidding. I do appreciate that Dr. Rosen decided to merge his textbook into a two-volume set recently. Thank you Dr. Rosen. For those of you who do not know Dr. Rosen, I’m going to read his bio from the UC San Diego Department of Emergency Medicine website. Here it goes.

“Dr. Peter Rosen was originally trained as a general surgeon and practiced surgery in the army and in Wyoming until 1971 when he became the first full time director of emergency medicine at the University of Chicago. While there he started a residency in emergency medicine. He then moved to Denver, Colorado where he was chief until 1989 when he moved to UC San Diego. Dr. Rosen currently divides his year between Boston where he teaches at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Tucson where he teaches at the University of Arizona and San Diego where he teaches at UCSD. His interest in emergency medicine has been in writing and editing and is still on the editorial board of the Journal of Emergency Medicine which he founded in 1983, and as co-editor of the Italian Journal of Internal and Emergency Medicine. Dr. Rosen’s major interests in emergency medicine have been in trauma, airway management, and resident education. He has edited and written a number of books and papers. His other interests outside of medicine have been in tennis, where he is determined to learn how to hit a four-hand, sailing, and reading.”

So now I’ve listened to many other interviews with Peter Rosen and can honestly say this is one you do not want to miss. We go pretty deep and talk about everything from Dr. Rosen’s morning rituals, his take on physician burnout, how he maintains a healthy marriage, some parenting advice. Who he thinks is the most successful person he knows, what books have shaped him personally and professionally, how two patients had such an impact on his career that he’ll never forget them, some of his regrets, when are you too old to be practicing emergency medicine, his views on podcasts, open-access journals, differentiating happiness versus fulfilment. The example of happiness he uses is the feeling of having a good bowel movement. Dr. Rosen ends with what he thinks he’ll never get to do in life and what he wants to be remembered for, and much, much more. This is Dr. Peter Rosen like you’ve never heard him before. So whether you are a medical student, resident, junior or senior level, attending, physician assistant, nurse, or someone not even in the health professions there is something for everyone in this episode. Let me say one more thing. Give this podcast a few minutes to get heated up. It takes a little while, really mostly me, to get to the more intimate parts of the conversation. That’s not saying that the beginning is not interesting. It’s just that the deeper material begins in the middle of the episode. So without further ado, let me introduce to you Dr. Peter Rosen.

Welcome to the Roshcast Dr. Rosen. How are you?

Dr. Peter Rosen: Alright. Nice to see you.

Dr. Rosh: Super. So it’s really great to be talking to you again. I was thinking this morning. This is the third time that we’ve actually spoken. The first time was back in 2003 when I was interviewing for a residency position in emergency medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess. The second time was in 2011, I believe. You were at the Legends of Emergency Medicine Conference at Detroit Receiving Hospital and gave a talk titled ‘Survival Attitudes in Emergency Medicine’ which had the room rolling in laughter. Really they were in awe. They were so impressed with that talk. Now this is the third time. So let’s dive right in. I want to get started with my first question. It has to do with ideals. So I’m approaching 10 years since I completed residency training at Bellevue Hospital. I really started noticing that I’m grappling daily with maintaining the same ideals I had when I started residency. Now I’m more familiar with the hidden agendas, and it feels like I’m not allowed to do what I set out to do in emergency medicine, which was care for the patient. So how does an emergency physician or really any healthcare provider maintain these ideals that first made us want to be emergency physicians?

Dr. Rosen: There’s no job that doesn’t have frustrations. I believe that the second law of thermodynamics applies to everything in life. That says in any closed system without an ever increasing infusion of energy, the system assumes maximum chaos. There’s no law that says that the infusion of energy has to be spent on anything useful. So in order to do the things in medicine that you set out to do that are fulfilling and that are the purpose of being there, you have to spend a lot of energy fighting off the things that aren’t any fun to do and that seemingly increase every year. I think what this means is that you probably don’t get an infinite run in any one place. I figure 10 years is the usual maximum, and then you have to move to another closed system and start all over again.

Dr. Rosh: You often talk about losing ideals as an emergency physician as you go through your career. So what I’m wondering is how do you struggle with, how do you manage maintaining your ideals throughout a long career in emergency medicine?

Dr. Rosen: When I first started in emergency medicine, I didn’t know it was a separate field. I was simply expecting to continue being a surgeon with emergency medicine being my administrative responsibility. But because of the animosity of the department of surgery—specifically the chair—I ended up being moved to the dean’s office. Then there was a gradual evolution of the notion that emergency medicine was a separate specialty. I probably had to learn it by doing it. I think that the ideals were that we would be able to train people to take care of emergency patients so that they would want to be there and would do a good job by being there. I think that the fights were mostly because once we demonstrated an interest—I use we not as the royal we, but those of us who were doing emergency medicine. Once we developed an interest in emergency medicine then all of a sudden everybody wanted it back. It was their turf and we were stealing their baby and their positions and their monies. They wanted to get rid of us. It was quite clear that after decades of neglect that it had to be done differently.

I think that my first recognition of the field is a separate specialty was that there was a different way of thinking about patients and a different set of responsibilities towards patients, and that had to be learned. Because it had to be learned then it was a body of knowledge that could be taught. My second goal, which kept me I think fulfilled in emergency medicine, was the recognition that without a literature the field wasn’t a field.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: It was about at that time after I had moved to Denver in 1977. I started work on the textbook in 1978. Then I started the Journal of Emergency Medicine in 1983, the year the first edition of the textbook came out. Of course we started writing papers. I also felt that our goal shouldn’t be to publish in the New England Journal, which didn’t want to publish anything related to emergency medicine anyway. It should be published somewhere that emergency physicians read because we were writing not for internists but for emergency physicians. I don’t think that everybody recognized emergency medicine was a separate specialty. Many of our enemies said there was nothing unique about emergency medicine, which actually was the source of some of my discontent. I wrote a paper called the Biology of Emergency Medicine. Probably the best paper I ever wrote because the dean at the University of Chicago told me that when he had his heart attack, he wanted a cardiologist to take care of him. Not an emergency physician. I asked him how he knew he was having a heart attack. He looked puzzled. I said we can’t have 47 different specialists sitting there waiting for a patient who knows what’s wrong with himself to come in and ask for one of them. Someone has to screen the field, which means deciding who’s the sickest, who has what problem that needs intervention. Also it’s a different process. Our responsibility is not necessarily a diagnosis so much as a recognition that we have an unstable patient who needs to be resuscitated and stabilized. Well, he didn’t understand, but that’s okay because I think those of us who practiced emergency medicine did.

Dr. Rosh: From that article, the Biology of Emergency Medicine—and I’ll post a link to that article. One of my favorite quotes from that article came from you. You said—and this is back in 1979— “The emergency physician must be as good as the cardiologist in running an arrest. However, after several recent experiences watching cardiologists in charge of an arrest, I say they must become as good as the emergency physician.” So that’s something I think that rings very true today. What has happened in emergency medicine that you would have never predicted happening 20/30 years ago that we now are faced with today?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I don’t believe I foresaw the development of the introduction of ancillary personnel practicing emergency medicine. I think our biggest threat to the field is the introduction of PAs and nurse practitioners. Not because I have anything against them, but because of the greed of the emergency physician. They’ve been asked to replace emergency physicians so that one could charge an emergency physician fee for their work but pay them a PA or nurse practitioners salary, which I think is not only immoral but probably illegal. I don’t think it’s right. If a PA can practice emergency medicine then why did we bother going to medical school, taking residencies, and taking as hard as we worked to describe and develop the field? I have no problem with using physician extenders for minor problems, but I don’t think it should be the physician extender that defines the minor problem. I think it should be a physician. I am very worried that once the government realizes that they can get away with putting a PA in place of a physician then they will stop supporting physicians to do the job that needs to be done. Claiming that it’s an equal success and that they’re practicing safe and good emergency medicine but they’re not.

Dr. Rosh: So the PA and nurse practitioner specialties are growing faster today than ever before.

Dr. Rosen: Well they are. I think that the original motivation for them was in institutions like large county hospitals where they didn’t have the money to support the number of physicians that they needed for their workloads. So they had to do something. As I said, I’m not opposed to the use of those personnel if it’s done correctly. What I’m opposed to is having them work side by side with the emergency physician. As I’ve seen in some community emergency departments, the PA’s doing all of the work while the emergency physician sits in the back room and plays solitaire on the computer. I think that there are cases that they should not see primarily. I think that there needs to be a direct communication between the PA and the physician on duty because you can’t expect someone to recognize problems that they weren’t trained to recognize. I’ll give you an example. I saw a case where a guy was hammering something on his recreational vehicle and felt something fly into his eye. He went into an emergency department where he was seen by a PA who didn’t know about the possibility of foreign body and thought the guy had a minor corneal abrasion, treated him as such, and sent him out missing the foreign body in the eye that ended up causing an intraocular abscess and causing lack of vision in that eye. I think most emergency physicians would have immediately obtained either an ultrasound or an x-ray of the eye looking for the foreign body. So I think that you can’t ask people to do what they’re not educated to do. If we don’t need the education of residency training and medical school then I’ve wasted my entire life.

Dr. Rosh: Sure. What is the greatest mistake we’re making in emergency medicine? Would you say it’s physician extenders or some other…?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I think that’s the greatest threat to emergency medicine. I think the biggest mistake is too much fragmentation into super specialized emergency departments. First it was pediatrics, now it’s geriatrics, then it was trauma. We forget that somebody has to be capable of doing broad based emergency medicine. I think a lot of our present graduates are headed towards critical care—and that’s good—but they are finding that it’s virtually impossible to combine critical care and emergency medicine. The more critical care they do, the less emergency medicine they want to do or they’re capable of doing. So I think we need to preserve the specialty of emergency medicine.

Dr. Rosh: So it’s interesting, right. So you trained as a general surgeon. I believe your father was a general internist.

Dr. Rosen: He was a GP surgeon.

Dr. Rosh: That’s right. So both of those specialists—internal medicine, general surgery—they went the way of becoming highly specialized. Right now we struggle with finding generalists. Given that emergency medicine is such—well it’s not so young anymore, but do you see it following that same pathway? It’s what you just described, right? We trained, we initiated. We began as this general field, and now we’re seeing this sub specialization.

Dr. Rosen: Yeah, I figure it’s inevitable, but I think we have to guard against it being the complete definition of emergency medicine the way it’s become in surgery. When I did surgery, a general surgeonist did a lot of different types of surgery. We did vascular, we did chest, we did GYN, we did some orthopedics. Today the general surgeon hasn’t got very many surgical problems left to do. They’ve all been taken off by the sub-specialists. I think there may be a pendulum swing back from that in the future simply because economically there isn’t enough to support a surgeon if he’s only going to do appies and gallbladders and hernias. I think there’s not enough economically to support a trauma surgeon when so few cases are actually operated on. So they end up becoming general surgeons again.

It’s interesting that the field has evolved in a different way in Europe where they have a trauma surgeon who is part orthopedist and part general surgeon. They do all the acute fracture work as well as the remaining trauma work. That’s worked very well in Austria and in Germany where they have trauma hospitals. I don’t see that happening in this country because it didn’t go that way, although it was an interesting idea.

Dr. Rosh: Right. So on the flipside, what do you think are some of the greatest growth areas in emergency medicine?

Dr. Rosen: Well, we’re taking over more and more of the immediate care of the patient. I won’t say acute care, but just the immediate care. I never thought I’d see the day where the emergency department did post-op care for same day surgery, but that’s what’s happening because the surgeon isn’t available. Obviously, the emergency department is still the only place you can get into the medical delivery system in any kind of expeditious fashion.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: I had a personal experience with this a couple of years ago. I had a bout of pneumonia. I called my internist who’s a very good internist and who I respected a great deal and basically wanted some antibiotics and some advice. I got a message saying that my call was important and would be returned within 48 hours. I turned to my son—the one who didn’t think I was a diagnostician—and said, “To hell with it, we’re going to the emergency department.” Sure enough an hour later I was admitted to the hospital. So I think that’s true of everybody, no matter what they’re funding. No matter what kind of primary care physician you have, you can’t get into the system in any fashion that’s quick other than by going to the emergency department. I don’t see that changing. So that means that we do all of the immediate care. We make all of the decisions about who needs to or doesn’t need to come in. That’s another interesting change. When I first started working in emergency medicine, I spent the bulk of my time trying to convince internists that patients needed to be admitted. Now I spend the bulk of my time trying to convince internists that their patients don’t need to be admitted because it’s late in the afternoon and they just bang them down to the emergency department to be admitted to the hospitals because they just want to go home. Those patients can be managed as outpatients. So we still serve as gatekeepers. We still are the safety net for the medical delivery system. We still have an important task of recognizing those problems that need acute stabilization and then worrying about diagnosis thereafter.

That’s led to one of the other acute problems in emergency medicine. I was telling the residents here in Tucson that the most difficult problem in emergency medicine today is acute ischemic coronary syndrome. ST elevation is easy. It’s recognizable and it goes to the Cath lab. Acute ischemic coronary syndrome if the patient is having persistent pain or dysrhythmia. If the patient’s pain has stopped then it’s difficult because we don’t have the evidence to know what to do for that patient and how fast to do it. It’s institutional dependent. In Boston we put those patients in the obs unit, do a stress test the next morning, and then have them followed by cardiology. In many places around the country, they’re sent home to follow up with cardiology and who knows how long it takes them to get an appointment. Who knows how long it takes them to get a provocative test or how safe it is to wait for one. So I think that we’re going to end up answering those questions in emergency medicine the way we’ve done in Boston. We’re going to take it over and say, “It’s not safe to wait. We’re going to do it before we send the patient home.” The reason we do that is twofold. One, it’s safer. Two, it is psychologically better for the patient. They don’t want to come in and be told, “You have a very serious disease. Go home the cardiologist will take care of it at some unknown time.” They want to know what to do for that very serious disease and what’s going to happen next. I think that’s up to us to help provide that information.

Dr. Rosh: Knowing what you know now, what advice would you give to your 20 year old self or your 30 year old self when you were just starting off in medicine?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I wouldn’t go into general surgery. I would go into emergency medicine. The reason is the emergency physician is what I dreamed a physician was. Someone who knew what to do when somebody had an acute need for a doctor. I think that I still believe that that’s a good thing to do in medicine. I don’t think everybody has to do it, but I think if your personality leads you towards wanting to answer that kind of question then emergency medicine is the place to do it. I certainly believe in residency training. I still dream that someday in all our country no patient will go into an emergency department and be cared for by anybody other than a trained emergency physician. I don’t think that will happen in my lifetime, but I think we’re closer to it than we were when I started in the field. I still think it’s a good goal to strive for.

Dr. Rosh: So I noted your certification expires in 2018. Are you planning to recertify?

Dr. Rosen: No because I don’t practice clinically anymore.

Dr. Rosh: Yeah.

Dr. Rosen: It’s funny because I just got back from Victoria, British Columbia where I gave a little talk on aging and emergency medicine. I think that the critical question about aging is when do you let go? When do you stop practicing? There’s no easy answer to that question. I think the safest answer is to have a mandatory retirement age and then break the rule when you have someone who doesn’t need to retire at that age. I also believe that there comes a time when you have to be intellectually honest and say, “I can’t do it anymore.” That time came for me several years ago. I’ve had some cardiac disease. I get unpredictable angina. I have this theory that the doctor shouldn’t be sicker than the patient.

Dr. Rosh: That’s a good one.

Dr. Rosen: I don’t like getting angina when I’m seeing the patient. I don’t think it’s fair to the patient. So I think there comes a time when even though it’s still fun to practice and I still dream about it, I had to admit that I was no longer comfortable in practicing. I didn’t feel safe. It’s not because I didn’t know emergency medicine. It’s not because I didn’t have experience in doing it. It’s because physically I couldn’t do it anymore. I think it was the only honest thing to do.

Dr. Rosh: So most things in emergency medicine have gotten easier for me. Recognizing disease patterns, dealing with patients, teaching. One thing that I find that’s gotten more difficult though is death telling. Having that conversation with the family. What experiences, what advice—Anything you have over the years that you’ve been able to grapple with that in a better way?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I actually did have a focused interest in that. In the first edition of my textbook, I co-opted the chapter on death and dying and grief counselling. I think you have to learn how to do it just as you learn how to do other things in emergency medicine. It’s uncomfortable because for the emergency physician, death is our failure. We believe that we can prevent untimely death, but of course that’s a relative truth. So we have to learn now to take care of the survivors. I could give an hour lecture on it but let me just quickly say the first step is the recognition that acute grief is sort of like being kicked in the testicles. It stops your whole world. All you can focus on is your loss. You have to allow people to get through that what I call fired spike. Then you have to help them turn their grief from a potential disease into a natural process. Some people want to eat. Some people don’t want to eat. I think the practice of sedating everybody who has an acute grief is not only a bad practice but is silly. You need to face the issue, not hide from it.

One of the tips that I have found that works the best is to remind people that there’s nothing wrong with remembering the good relationships that they had and forgetting about the fights. One of the reasons for the grief spike is that we all feel guilty about the things we never got around to doing with the dead person. I think we should remember that death robs us of a future but not of a past. There’s nothing wrong with sitting in our living room and thinking about conversations that we’ve had. I still have mental conversations with friends that I’ve lost because I can hear their voices in my head. That’s helped me with my own grief, and I think that helps other people with theirs.

Dr. Rosh: Thank you. So when is the last time you’ve changed your mind on an important issue and what was the issue?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I change my practice all of the time when I find new evidence upon which to change it. I used to think that all pneumonia had to be admitted. Then I discovered that, in fact, unless the patient is unstable there is no reason not to care for them at home. I suspect there’s a lot of disease which we were very rigid about approaching. PE may be one. Canadians have shown us that PEs don’t all need to be admitted. It’s probably safe to manage DVT and PE patients who are stable at home. So I think that there are many areas such as that upon which I’ve changed my mind. I’m willing to change my mind if you could show me a safe alternative to what we were doing as a standard.

What I am unwilling to do is to change my mind when the change is for changes sake and they’re asking me to change to something that doesn’t make any sense, like not operating on appendicitis. Appendicitis is not an infection. It’s an obstructive disease. The reason that you can get away with not operating on it some of the time is because the untreated mortality of appendicitis is only 30% before they were ever doing surgery on it.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: Well if 7 out of 10 patients relieve their own obstruction and get better then of course it looks like you don’t need to operate on it. It’s that other 30% that do go on to need surgery who often have complications of that disease process and they end up dying when they don’t need to. I think we’ve solved the problem of appendicitis with a very simple operation. Why should we stop doing it? Those are the kinds of changes that drive me absolutely crazy in medicine. I think the motivation is monetary. It’s a very silly way to try to save money because you end up spending a lot more when the patient fails as an outpatient. It’s unfair to the patient. A classic example is Rafael Nadal. They didn’t operate on him so he could “finish his tournament”. He didn’t finish it because he ruptured his appendix. So then he ends up having to have two surgeries. He has a year of trying to recover from an intraperitoneal abscess and it nearly ruined his career. Had they just said, “Okay, this tournament is over for you.” He could have had a lap appendectomy, been out of the hospital in 12 hours, and been back to his top athletic form in probably a couple of weeks. So I think that it’s a very silly idea.

Dr. Rosh: Gotcha. So one change that’s happening in education is the move from the traditional textbook to a more online open-access education. Now I’d imagine you have an opinion about this.

Dr. Rosen: Well, I do. There are several things in your question that make it separate issues. The first is open access journals. I really am very opposed to that. The reason is not because it actually provides greater access to medical information because I don’t think it does. What it does do is it takes the cost of publication away from the publisher and puts it on the back of the author. Now that may be fair, but it is unfairly putting it on the back of junior authors because of the open access journals allow the senior authors to pay that access fee with their research grants but the young authors don’t have any. Therefore this lowest paid faculty, the young faculty, have the highest cost to publishing the work that will get them research grants and get them the higher salaries. So I think it’s very unfair.

Secondly I don’t have any problem with publishing journals electronically. I think every major journal does do that. I think there are portions of the journal that are better published electronically than on paper, such as case reports, because illustrations can be done in color which are prohibitively expensive on paper. I still think there is a need for paper publications. And in textbooks, the search engines just aren’t that good. I think there needs to be a place where you can sit down and read a complete discussion of a topic along with footnotes, along with the ability to switch to other chapters quickly, which is not electronic reading. So I think there’s a place for both. I think that it interests me as I talk to you that people who are now editing Rosen, they still get a lot of requests for a paper textbook. What people want in a textbook is something that the podcasts are giving them, and I have a little concern about that.

Dr. Rosh: So tell me about that.

Dr. Rosen: They want the textbook to be directive. I have no problem with that. Where there’s controversy and there’s not enough evidence to tell you what to do then take a position. Say on the basis of what our current experience is, we can’t prove that this is the best method and we’re willing to change it when there is evidence, but in the meantime this is our approach to a problem. The problem that I have with podcasts is that many of the residents would rather listen to a podcast than read a journal article or a textbook. What they’re getting is medical expert opinion rather than medical evidence. I don’t have any problem with, as I said, a place where the evidence is not there, but I see a lot of the podcasts taking positions that are not safe because that’s the position of the podcast maker. Now I’ve contributed to podcasts. I don’t have any problem telling people what my style is and why I chose my style, but it’s not a substitute for reading what evidence is out there and making up your own mind.

Dr. Rosh: So can you predict or what’s your opinion on the impact that the internet, podcasts, blogs, snippets of learning is going to have from our residents now, medical students, for when they’re practicing? Or is it going to have any?

Dr. Rosen: I think they’re going to discover that at some point they’re going to have to do the work. You can’t take Rosen and put it under your pillow and learn it. You have to read it. You can’t take medicine and learn it through someone else’s opinion. You’re going to have to study it, you’re going to have to compare your experience to what the literature says. You’re going to have to discover that the populations that are studied in research projects are not necessarily the populations that you treat in your practice and therefore you’re going to have to modify your practice. So you’re going to have to grow up and be a mature physician just as we all did. Our education didn’t finish when we completed our residency, but it gave us a structure from which we can improvise. It gave us a means of starting. It gave us a methodology for being safe in our evaluation of patients, and it taught us what were the responsibilities of our job which are not necessarily to make a diagnosis. We need to remember that. When a patient comes to the emergency department, you want to find out if he’s dying. There’s only five ways you die. There’s a billion ways that set you on the pathway to death. You don’t really care how you got on the pathway. You do care the patient’s on that pathway and can you do something to get them off that pathway and back on the road to health. Then and only then do you start worrying about diagnosis. I think when we start worrying too much about diagnosis we turn into internists and do a bad job of emergency medicine.

Dr. Rosh: I’m interested to hear, if you have this, the five ways that the human body dies.

Dr. Rosen: Well you can’t breathe, you lack oxygen for one or more reasons, your heart can’t beat, or your heart has nothing with which to beat, and there’s metabolic failure, or the brain doesn’t work, the nervous system. So which of those systems is under threat. Sometimes it’s more than one. Obviously, one will lead to many. There is, in my mind, a very curious phenomenon that happens as you die. There has to be a messenger of death within the body. Something tells the cell that it’s time to destroy itself, what we now call apoptosis. What is that something? We still don’t know. Why is it that some people die, and others live with injuries or diseases that would seem lethal? I’ve never been able to answer that question. I think it’s one of the things that makes emergency medicine continue to be exciting in a puzzle. That is why we can save some patients but not others. I joke that there are three kinds of patients. There are those that are doctor proof. No matter what we do to them, they’ll get well. There are those who are doctor insensitive. No matter what we do for them, they’re going to die. Then there are those who are doctor sensitive. If we don’t do what they need and do it quickly, they’re going to turn into group two. We’re going to get blamed for group two so we might as well take credit for group one.

Dr. Rosh: Right. So what’s the greatest impact a patient has had on you?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I’ve had many throughout my career. I would say the two patients I remember the most. One of them was a 42 year old man who came in complaining of shoulder pain. He’d had an acute onset of it as he awakened that morning. When I examined him, he had a clear rotator cuff tear. I x-rayed him, couldn’t find anything. I was about to sling him and send him to ortho for follow up when I finally asked the right question, which was how does a 42 year old man get a rotator cuff tear in his sleep. I went and said, “Did you bite your cheek last night?” He said, “Yes, how did you know?” I said, “Did you wet your bed last night?” He looked terrified because he wasn’t going to tell me that. He lived alone and was very ashamed of it. I ordered a head CT and he had a meningioma, and he’d had a seizure of course. That case has stayed with me for many years because it is the classic definition of emergency medicine and why diagnosis isn’t enough. You have to understand that part of your job is why did the patient develop this disease today? What’s different about the patient? That’s what I have to intervene in.

The second case was a young boy who was 15 years old who was riding with his father in a car that was struck by a drunk driver. I had to take care of this boy at a time when my youngest son was exactly his age, and this kid looked like a clone of my son. It was emotionally very difficult for me to take care of this boy because it was like taking care of my own boy. Of course, I had to do things that were painful and unpleasant. He did have a positive peritoneal lavage, which is what we were doing at that time. He went off to the OR and did quite well. I remember when my wife picked me up after my shift I burst into tears because it was so hard to take care of somebody who was like my own son. I think that’s made me realize that there are emotional impacts on us in emergency medicine that we’re often not aware of and yet we have to continue to perform despite those emotional impacts.

The one area that I think we have to remember and improve upon in emergency medicine is making people feel better. We focus on the critical patient. Those are easy. You plunge a tube down every orifice, and you admit them somewhere, but it’s the patient who’s going to go home that’s the difficult patient. We have figured out that it’s safe for them to go. We have figured out what their acute problem is. Now we have to tell them how we are going to make them feel better. We’re going to lead them glad that they had us as a doctor and glad that they came to the emergency department. We’re very bad at that. We’re very good at telling them you know, it’s not your gallbladder. You don’t have a PE. You don’t have cancer. Well, the patient didn’t think he did in the first place. He didn’t know what he had. That’s why he came to the emergency department. Well what do I have and how do I get over it? That’s what they need to hear from us. We need to spend a little more time doing that and thinking about that as part of emergency medicine.

Dr. Rosh: In your experiences, what’s been the greatest reward for interacting with patients, for treating patients for you? Personal reward.

Dr. Rosen: Lewis Thomas said that a good doctor has the gift of affection. I can’t put it any better than that. I love taking care of patients because I always, from the time I can remember as a little boy, wanted to know what to do to make people feel better when they had an acute need to feel better. I think it’s that satisfaction. The recognition that now I know the answer to a lot of those questions—not all because you never can—but a lot of those questions. In fact, I can do the very thing that I find fulfilling which is to take someone who’s anxious and worried and feeling bad and help them to feel better. That’s what a doctor’s all about and that’s what I wanted to be and that’s what I became.

Dr. Rosh: Are there any lessons that you learned from your father that you still think about? One or two or three lessons?

Dr. Rosen: Well he was really good at making people feel better. I remember I was spending a summer in his office when I was a medical student. He had this machine that made a lot of noise and it sprayed and it sucked. He used to spray sore throats with some really nice tasting stuff. I, being the smartass medical student, said, “I read a paper that said it doesn’t help sore throats to spray them topically.” He looked at me and he says, “You know that, and I know that, but the patient feels better. If the patient feels better then he pays my bill and I pay your tuition.” Which he didn’t do by the way. That was the lesson that has always stuck with me. He was really good at that. It’s not that he was being dishonest. It’s that he was really concerned that patients would feel better when they left his office. He had a consultation room. Every patient, no matter how trivial the problem, had to sit with him in that room before he went home to answer any questions, to get the instructions, and to leave feeling that this doctor had really taken the time to put some personal interest into him. You can do that in the emergency department without a consultation room. You just have to make yourself do it.

Dr. Rosh: Any other lessons that you can think of?

Dr. Rosen: I think intellectual honesty. There’s no substitute for recognizing what you don’t know. It’s okay to share that with patients. I don’t know your diagnosis. I can’t know it because this isn’t the place to find it out. I do know what’s happening today and I do know what we’re doing to make you feel better, but there are many things that I can’t do here in the emergency department and I’m going to share some of them with you. I think that the intellectual honesty to say I need help and not try to do everything by myself. I think the intellectual honesty to say it’s time for me to stop practicing. It’s time for me to cut back from my practice because physically I’ve aged, and I can’t do it anymore. The honesty to say I’m sick today and I have to do something that isn’t part of my culture, which is to get a substitute for myself because I’m really not in the right condition to take care of patients. The honesty to recognize that I have to prepare myself to go to work. That I can’t go to work tired. I can’t go to work with too little sleep. I can’t go to work after having a major quarrel with my spouse and do a good job. That I have to take care of the practice as well as of myself.

Dr. Rosh: So see if you can answer this one. What is something about you that most people don’t know?

Dr. Rosen: I don’t know how to answer that question. I would guess that they probably don’t know how much I read.

Dr. Rosh: Science, fiction, non-fiction?

Dr. Rosen: Everything, but I read a lot of science. I probably read between six and twelve papers a day. In large measure because it’s part of my editing responsibilities, but in large measure it’s because that’s the only way I feel comfortable that I know what I need to know in medicine. I like to read non-medicine because it gives me a picture of my culture and what people think about their society which changes over time. It gives me a chance to find out about different generations of people in my society and what are their concerns and what are their fantasies. Finally it gives me pleasure. I’ve always been an avid reader. Even in medical school I probably read a novel every two or three days. Probably should have been reading a little more medicine but it was too boring.

Dr. Rosh: So can you give us one, two, three of the most influential books that you’ve read? Maybe that have influenced, let’s say, something that’s influenced your personal life, something that’s influenced your professional life.

Dr. Rosen: Well the novel that I like the best was The Red and the Black by Stendhal. I wish I’d read it when I was 15 because it’s sort of a young man growing up and how the world looks inside of his mind and how he drives himself to do what he thinks he ought to be doing as opposed to what he really wants to be doing. That he is quite old before he discovers that that’s really what makes a man. Not to do what everybody thinks makes a man, but to do what you ought to be doing as a man. Not what you ought to be doing because of what the people around you say. I think that Stendhal did that in such an interesting fashion because he wrote the novel through the eyes of his characters. There is a story line that’s what’s happening to the characters, and then there’s a story in the minds of the characters that’s totally different. Their vision of what’s going on in that external storyline. It’s brilliant. I don’t know any other book that does that. He does it better than I would have thought it was possible to do. So that’s one of my favorite novels. Anybody who wants a good read should read that one.

Dr. Rosh: Yeah. We’ll put that with the show notes. We’ll put the title and a link to it on Amazon.

Dr. Rosen: The medical book that had a profound effect on me was called Horse and Buggy Doctor. I read that as a kid. It was a story of a GP and how he got to be competent in medicine. He went to Austria to study because that’s what doctors did in those days. What I got out of that book was not so much how he got to be a doctor or what he did as a doctor, but there’s one chapter where he taught himself how to do tonsillectomies by practicing on cadavers. That stood out in my mind that you have to teach yourself how to be competent. I remember doing the same thing when I was a surgical resident. It wasn’t tonsillectomies, but we had a month on pathology where I did autopsies. I was less interested in the autopsy than I was in practicing the operations that I was going to be doing on people. Again, it was a very important book for me because it sort of was my first glimpse of the real world of medicine as opposed to the other novels about physicians like the Frank Slaughter novels. I think Lewis Thomas’s book The Youngest Science had a big effect upon me too because he talked about what a doctor is, and not very many people do that. I’d love that aphorism. A good doctor has the gift of affection. I couldn’t say it any better.

Dr. Rosh: He wrote The Lives of Cells also, I think. Was that him?

Dr. Rosen: He did.

Dr. Rosh: Did he write the Snail and the Medusa? Something like that.

Dr. Rosen: I think he did. I think he did. Oh no, no. That was Gould. The paleontologist at Harvard.

Dr. Rosh: So are you reading anything now? Anything on your nightstand? Anything recently that you’ve read?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I read about 10 books at the same time. So yeah. There’s a lot of books on my nightstand.

Dr. Rosh: Have you always done that? Have you read multiple books at a time?

Dr. Rosen: Yeah, I’ve always done that. My granddaughter put me onto a book that’s a new cult novel.

Dr. Rosh: What’s it called?

Dr. Rosen: An Infinite Jest. It’s about a kid who’s going to school in a tennis camp. I guess the author was a ranked junior tennis player. He later became a professor of literature and writing. I think it’s a cult novel because he ended up committing suicide. The novel is sort of in part about that character and in part about characters who are addicted to alcohol and drugs and who are depressed. It’s sort of like a combination of Tom Robbins, Neil Stevenson, and O’Toole, the guy who wrote the other cult novel called A Conspiracy of Dunces who also committed suicide. I can’t say that I like or dislike the novel. It’s extraordinarily long. It has a zillion footnotes and I’m only about halfway through it, but it is well written. Although, I think it could have withstood a savage editing. It didn’t need to be quite that long. Many of the footnotes are just sort of repetitions of the rant the footnote is based on. It does give you a picture of what people are feeling inside themselves as they experience various things in their lives. Having spent a lot of my life taking care of alcoholics and drug addicts and depressed people, I find it very accurate. So I think it’s a very interesting book. I like to read history. I just read a series, a kind of trilogy, about Cicero and the historical novels of ancient Rome, which I think are pretty accurate from what I’ve learned about that time.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: Let’s see what else I’m reading. I like to read no brainers because then I don’t have to put out a lot of brain energy. You know spy novels, mystery novels.

Dr. Rosh: Have you thought about writing—Other than a textbook, have you ever thought about writing a nonfiction book or a fiction book?

Dr. Rosen: Well I have, but I chose not to earlier because I have a son who’s a writer. I don’t compete with the professional careers of my sons.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: I learned that when my oldest son who was in law school. We were talking about constitutional law, which I’ve always been interested in. I was discussing it with him because I’d read a couple of books on it. My wife said, “Why don’t you go to law school?” He got very angry. He said, “Why does he need to do that? He has a profession.” I realized he wanted to be the lawyer in the family. I quickly said, “Why do I want to go to law school? I’m a doctor.” Then I realized that it’s hard on your children when you compete with them at places where they’re trying to be individuals. I realize that I’m probably not the easiest person to be a son of. So no, I haven’t wanted to write. Now I’m old enough to the point where I’m not sure that I want to undertake the work of writing. I still like writing on medicine. I like writing editorials. I still write papers now and then, and I do a lot of editing. So that takes care of my literary itch.

Dr. Rosh: Do you ever gift books to people?

Dr. Rosen: I do. All the time.

Dr. Rosh: If so, what are maybe the top one, two, or three books that you have gifted over your life?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I don’t do the same books. I give books topically to people on a subject that we’ve been either arguing about or discussing or that I’m currently interested in. I give books to people that I’ve enjoyed that I hope they will enjoy. I give books to people on topics they’ve asked me about. I know some book that will meet their need. So I can’t say I’ve given the same book that often.

Dr. Rosh: Do you have one that comes to mind—one or two—that is kind of your go-to?

Dr. Rosen: Well when people ask for a good read I give them The Red and the Black.

Dr. Rosh: I’m going to pick that up. When you think of a successful person, who comes to mind?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I define success as being fulfilled, not being happy.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: I think happiness is physiologic. It’s having a good bowel movement. It’s not something that you really control. I think fulfilment comes from something that you had to do in order to make it work. My nephew Rich Wolf is a successful man. I’m very impressed with the way he runs his department and with what he’s done in his life. You know, I have a circle of academic companions and friends and I’m very impressed with how smart they are and how well put together they are. Guys like Dave Brown at Mass General and Sam Kime here at Arizona and Ted Chen in San Diego. I’ve had the pleasure of working with some of them as residents, the pleasure of knowing some of them for years and sharing my vision of the world through my special kind of academic needs with them. All of them have one thing in common. That is they are intellectually honest, and they work hard enough to have accomplishments that fulfills them. I think that’s my definition of success.

Dr. Rosh: Do you still set goals? Did you set goals for yourself as an early junior physician? As a mid-career physician?

Dr. Rosen: I think sort of globally I did. I set out to be a doctor. That was a goal that didn’t come easily. I didn’t get into medical school the first year that I applied, but I managed to succeed. I think that that was probably the goal that was most important to me. Had I not become a physician I think I would have considered myself a failure. Since I did, I don’t know for sure. Maybe I would have grown up. I obviously set a goal of training as a surgeon. I didn’t know I was changing specialties when I moved to Chicago, but I set my goal to solve the problems of the emergency department. I think those are the kinds of goals that I set, problem solving. I think that at some point in my life I realized that there were things I wasn’t going to be around to and that it was okay. I think before that I probably was a kind of driven person. I don’t know what changed. I don’t know why I stopped feeling that. Maybe it was the recognition that I was older and that there were things that I just simply couldn’t do and therefore it was time to stop worrying.

Dr. Rosh: Could you tell us some of those things that you think that you may never get to do?

Dr. Rosen: Well some of them are travel. I’ve always wanted to go to China. I’m never going to do that. I always wanted to do some basic science research, but I never got around to it. That may well be because I don’t have any talent for it, and I was fooling myself. I always wanted to study more mathematics. I did for a while as a hobby, but again I never got around to making a formal study of it.

Dr. Rosh: Is there anything that people don’t ask you that you wish they did?

Dr. Rosen: Well, I think that what I wish for people is that they would stop iconizing me. They have an image of what I must be because that’s what they think I am. I’m probably no where near what they are thinking. So I suppose the answer to your question is I wish they would accept me as a simple person as opposed to an important person, which I’m not. One of the medical students who was interviewing for residency asked me what I wanted to be remembered for and was quite shocked when I said my sense of humor. I really meant it.

Dr. Rosh: Right, yeah. Some people don’t know.

Dr. Rosen: No. I think people are often surprised by my sense of humor.

Dr. Rosh: Yeah. Do you believe people have a specific calling?

Dr. Rosen: I think people have certain talents. If they’re lucky, they find a way to express those talents. I was unusual because none of the members of my family ever felt it, but I grew up knowing I wanted to be a doctor. That was very helpful to me. I don’t know that it helps other people to grow up thinking that they want to be an x and then becoming that. Although it’s interesting how many of the sons of people in certain fields take on those fields. I think that we are products of our early socializations and trainings. I don’t know that there are such things as natural doctors, natural lawyers, natural architects. I do believe that people have different talents in medicine. Not everybody is capable of being an emergency physician. I think it requires somebody who’s not afraid to make decisions and who’s not afraid to act. There are physicians who need more time to make a decision, who need more information, who don’t mind steering a truck but are afraid to get it moving. They don’t belong in emergency medicine. I do believe that there are physicians who are not very good with people. They probably don’t belong in emergency medicine either.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: So I think we have to find out where our talents lie and then try to utilize them profitably in a field that calls for their use.

Dr. Rosh: In both your personal and professional life, is there one thing, two things that you’re most proud of? You’ve expressed a lot—healing patients and your sense of humor. What are you most proud of both professionally and personally?

Dr. Rosen: I think all of the people that I’ve helped develop. That’s both professional and personal. I am, of course, proud of my efforts to produce literature, but I think I’m most proud of my graduates. In my personal life, I’m most proud of the fact that I will have been married for 57 years this May. That I still find my wife to be my best friend and someone who I can make laugh. Someone who I’m very happy to be around, someone who I’m friends with who I need to see every day. I’m happy that I didn’t make enemies out of my children the way that my father did, and I’m happy that I have a chance to see my grandchildren grow and develop. For example, my oldest grandson is in college and he often sends me his papers to edit, which I get a kick out of. He’s actually a very good writer.

Dr. Rosh: So some people may say one of your greatest achievements is being married for 57 years. I’m at 10 years and have struggled at times and have to work much harder at maintaining a relationship than I had ever thought. In the end, the investment is certainly well worth it. How are you able to maintain a marriage for almost 57 years? How do you keep it going? How do you maintain that? What advice do you have?

Dr. Rosen: Well, it’s rather similar to how you sustain yourself professionally. Number one, you hit the nail on the head. It’s something you cannot take for granted. You have to work at it. Number two, you have to invest the energy to keep it from becoming chaotic. By that I mean I look back on my early years of marriage and I was a selfish prick. I was worried about being a competent physician. I didn’t have time for my wife and children. I think that that’s one of the things I regret the most because I realized that there were ways to do both and that I would have been better at what I most wanted to be by taking the time for my wife and children. Now how do you do that? Well, one way is with manners. I couldn’t be bothered to call home that I was going to be late because something had come up because my wife knew I was doing something important and I didn’t have to tell her. I discovered over time that taking a minute to make a phone call made an enormous difference to her. It’s not that she wasn’t willing to let me do the things I needed to do, but then she could go on with her life knowing where I was instead of waiting around wondering what was happening. I think it took me about 25 years to learn how to apologize when I didn’t feel I was wrong. I would suggest that as an important tactic for two reasons. It stops the vicious cycle of anger. You did something to me; I’m not going to apologize. You need to apologize to me. So I’m going to do something in my anger that will get even. Instead of which if you apologize and you know you’re not wrong, it opens the conversation on a level of what is it that bothered you and I can tell you what it is that bothers me. Every time I’ve done it within 48 hours my wife has, in fact, told me that she too wanted to apologize.

Dr. Rosh: Right.

Dr. Rosen: So it really is a way of smoothing over something that could become a source of pain between you and you don’t need that. Number three, you’ve got to tell people that you care. You can’t take them for granted. You’ve got to tell your children that they’re great kids. You’ve got to tell them why you’re mad at them. You’ve got to tell them why you’re proud of them. Similarly with the wife, you’ve got to tell them you love her. It’s not enough to do it. It has to be expressed. There’s nothing wrong with doing it with a surprise now and then. Give her an orchid or say we’re going out to dinner tonight because you’re working too hard. It’s the little things that make her realize that you really do have deep feelings for her. It helps you to preserve the relationship that has to be more than sexual. If there isn’t a friendship between you, you can’t share a life together.

Dr. Rosh: Yeah. That’s something that probably took five years into my marriage to really grasp. We end up taking for granted the people who are closest to us and who we supposedly love the most. I think going into medicine where the demands of both time and energy and focus are so great that it was about five to seven years into that where I recognized that and was able to make that change also.

Dr. Rosen: Yes. I think that’s very important. Also to realize that things aren’t that critical. That you don’t have to finish that paper today. I was particularly bad at that. I always was rushed to do more things for my career, but your career will flourish if you publish that paper tomorrow as opposed to today. Now, I don’t mean put it off until next year. I mean take the night off and go out to dinner. You’re not going to destroy your career and you are going to help your marriage. I think that you can help yourself too because you’re going to get something back from that friendship that you desperately need. I think that you have to understand that you grow together. That different things happen over time. You have to make sure that they’re happening simultaneously. Just because you’ve been married 20 years doesn’t mean that you can’t grow apart from your wife and then one day discover that you’re unhappy with being in that situation. I think you have to guard against the kind of selfish curiosity that most men possess.

Dr. Rosh: Yeah.

Dr. Rosen: I’m entitled to something new and something different. Well, no you’re not, and you don’t really need it anyway, but we think we do. I think that part of that is to keep your wife as something you really care about. That’s what’s fresh and new. See her in a different light. Take her to a new place. Discover things together on a trip somewhere that that’s your private property, that little restaurant that you fell into. If you don’t keep working at it, I can assure you that your marriage will crumble and fail.

Dr. Rosh: Yeah, yeah. Do you have any favorite quotations or anything that you keep in the back of your mind or you look at or you read over and over again that you can recite now, or do you have to reference something?

Dr. Rosen: I don’t use quotes in that respect. My quotes are mostly sarcastic humor. I love Winston Churchill for example. His quick wit is something I have a great envy for. I think one of my favorite quips was Richard Burton was having a fight with some earl who told him that, “You are a scoundrel and will die either of syphilis or by being hung.” Burton said, “Probably true depending upon whether I embrace your wife or your moral.” That’s one of my favorite. I think the more meaningful quotes I find hard to be apt in more than a single situation. I probably spout them from time to time from the things I’ve read, which is, “When it comes to stupidity, even the gods weep.”

Dr. Rosh: Right, right.

Dr. Rosen: Most of my quotations are either stolen quips from people that I like the sarcasm of or the humor of.

Dr. Rosh: Gotcha. I know we’re coming to an end soon. I know you have some meetings shortly. I wanted to ask you. When you were early in your training throughout your career, did you ever have any morning rituals? Did you ever have a specific time you’d wake up in the morning, things you’d do before you get to work or anything like that?

Dr. Rosen: Well, not really because I hate getting up in the morning. Of course, as an emergency physician I’ve spent most of my life doing it. So my morning ritual was how the hell do I wake up? I think probably the closest I come to a ritual is shaving with a brush and a razor because it takes a little time and it kind of gets me a chance to wake up a little bit.

Dr. Rosh: When would you do most of your writing?

Dr. Rosen: I’m a late night person. I do my writing mostly in the evening or at night.

Dr. Rosh: So before we wrap up, we have a lot of great pearls in the conversation. I’m not sure we really need anything else. Is there anything you would leave this conversation with to tell maybe a medical student today, a resident, junior, faculty member that you wish someone would have told you?

Dr. Rosen: Yeah. I think you have to work at preserving your ideals in your profession just as you work at preserving your love for your wife. I’ve never met a medical student candidate or a resident candidate who didn’t have ideals who didn’t lose them through medical school or five years later. I think part of that is pseudosophistication. Part of that is because you didn’t try to keep them. Why did you become a doctor? Why did you become an emergency physician? What did you expect to get back from it? I believe that those of us who think we can be perfectly altruistic are naïve. Either that or dedicated Christian. What selfishly did you expect to get back from being an emergency physician and why are you no longer getting it? Are you taking care of the wrong kinds of patients? Because there are different practices in emergency medicine. Are you in the wrong group? You don’t like your partners and their attitudes towards money or medical care. Are you in the wrong kind of practice because you really don’t like academics. You don’t want the pressure of producing academic product. You don’t need to. Go practice in the community. Do something different. I think you have to ask what it is that fulfills you, why it’s no longer fulfilling you, and what you have to do differently in order to get that back. It may mean a change of specialty. It may mean a change of city, or it may mean a change of the kind of practice you do. It will certainly mean loss of money because you can’t make change without a cost, but only you can make that change. You’ve got to do it because the second law of thermodynamics is it. When you can no longer come up with the energy necessary to preserve the order of your system then it’s time to move to a different closed system. I think you’ve just got to accept that, but you’ve got to work at it.

I think the people who hate what they’re doing but won’t change it are the ones who claim they’re burned out. They’re just feeling sorry for themselves. Maybe there’s a good reason for they’re not getting back the kind of recognition and reward that they thought they were going to get. Maybe they’re not earning the income that they thought they needed. Whatever’s lacking, only you can change it. I don’t believe in burnout. I think that what you’ve got to do is say what am I missing? What do I need to do differently? Is it them or is it me?

Many of the moves I made I never thought I would make, like leaving Denver to go to San Diego the first time but it was fine. It wasn’t easy. I resented having to do it, but it turned out to be a very good move in both the short and the long term. I took a long walk on the beach and I said what do I owe them? Am I not getting it? Is it them or is it me? It’s them. I’m leaving. It was triggered by my wife saying to me one day, “Why are you always so angry when you come home from work?” I started ranting and she said, “That’s exactly what I mean.” She was right, of course. Why do I need a job that makes me angry? What do I need to change so that I won’t get angry? Is it me? I’m just turning into a crusty old man who can’t get his way and therefore loses his temper, or is it because the things that I’m trying to accomplish are not any longer possible in this environment? It turned out to be the latter, so I moved to San Diego. So that’s what it leaves you with. Preserve your ideals. Don’t let the people around you poke fun at them. Look for where you get your fulfillment and make sure that it’s still there and go after it if it’s not.

Dr. Rosh: That’s exceptional. Thank you. Thank you Dr. Rosen.

Dr. Rosen: Thanks for the opportunity to talk with you. I wish it would happen more often.

Dr. Rosh: Thank you. Thank you for your time.

Dr. Rosen: This kind of podcast I don’t mind. It’s when I pontificate and tell people how to practice medicine without any reference to evidence. Those are the podcasts I hate.

Dr. Rosh: Hopefully, we did some justice with this one. I think it came out really well. So thank you and we’ll talk soon.

Dr. Rosen: Okay.

Dr. Rosh: Hey guys. This is Adam. Thanks again for listening. If you liked this episode, please go to iTunes, and rate the podcast and leave a review. Every positive review helps. Also, remember to subscribe to the podcast so you automatically get episodes downloaded to your podcast library. Please send any questions or feedback to the email conversations at roshreview.com. If there’s someone you have in mind who you’d like for me to have a conversation with, please let me know. Don’t forget to check out the Rosh Blog at roshreview.com/blog for more excellent content. If you are a student, a PA, nurse practitioner, or doctor who is in a training program or residency or has an upcoming exam, take a look at roshreview.com and sign up for a free trial. Thank you again for listening and I’ll see you at the next episode. So long.

Get Free Access and Join Thousands of Happy Learners

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments (0)