How to Increase Your ABFM Family Medicine Certification Exam Score by 100 Points

This article covers two easy strategies to help increase your score for the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Family Medicine Certification Exam or In-Training Exam (ITE). While there is no magic pill or wand that will increase your score, these two techniques are useful, easy to implement, and only require a little of your time.

The first strategy is to identify what you don’t know. Sounds easy, right? The key is to go through a curriculum and identify what you don’t know—not what you are weak at—but what you don’t know. The second strategy is to take advantage of human error. Tests are written by humans, and humans make errors from time to time. By paying attention to five types of flaws that question writers make, you can narrow down an answer choice to either the correct answer or a 50/50 probability, even without knowing anything about the topic. By combining these two strategies, you’ll be able to increase your Family Medicine Certification Exam score by 100 points, which could be the difference between passing or failing. Let’s get started.

Strategy 1: Determining your unknown unknowns

As you begin to study for your exam, you’ll find that there are areas you are comfortable with. Maybe you have a special interest in endocrinology and feel confident with any question that might be asked on arginine-vasopressin disorder (diabetes insipidus). Because you are confident in endocrinology, you spend less time reviewing it. This is one of your known knowns. There is little utility in spending too much time on your known knowns when preparing for your exam.

During medical training, my understanding of liver disease was poor. Hepatic encephalopathy was just a term to me. I did not understand how or why it occurred, and I had a poor grasp on managing the condition. Liver disease was a known unknown. Because I recognized this specific deficiency, I was able to target my learning to diseases of the liver.

Once I started to focus my learning, I came across many concepts and ideas that I knew nothing about…never even heard about some of them. These were the unknown unknowns, a concept created by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham. It is part of their “Johari window,” a tool that helps users identify blind spots about themselves and others.

Known unknowns are things you’re aware that you don’t know—you can recognize that you don’t understand them. Unknown unknowns, however, are unexpected because you don’t know they exist.

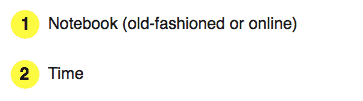

The way to supercharge your ITE or Family Medicine Certification Exam score is to identify your unknown unknowns. It takes a little effort, but the steps are rather easy. All you need are two things:

The system works like this.

Step 1: Answer a question from a question bank. If you get the answer wrong, read the explanation. Then write down in your notebook the part of the explanation that describes why the correct answer is correct. This process helps to identify your unknown unknowns. Subsequently, if there is any other information that you did not know or somewhat knew, record it as well in your notebook under the same topic.

You should do this for every question you get incorrect. I also encourage it for questions you may have answered correctly but discovered new information in the explanation that you previously did not know.

Step 2: Start each study session by reviewing your notebook that contains your unknown unknowns. As you do more questions, you will get questions wrong on topics already recorded in your notebook. For example, if you answer a question incorrectly on which age group most commonly gets de Quervain tendinopathy, you’ll record in your notebook something like “de Quervain Tendinopathy: Epidemiology includes women between 30–50 yrs old and postpartum.” Two weeks later, if you can’t name the diagnostic test characterized by thumb flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist, you should go back through your notebook to find your first entry on “de Quervain tendinopathy” and add the “Finkelstein test” as the way to diagnose the condition. While we are on the topic, here is a cheat sheet for de Quervain tendinopathy.

After a month or two of recording your incorrect answer explanations, you will have a filled notebook of your unknown unknowns and maybe many of your known unknowns. If you do this on a consistent basis and get through 1,000 to 2,000 question bank questions for a 300-question standardized exam, you’ll identify most of your blind spots that questions can be asked about. You will convert your unknown unknowns to known knowns.

Here is how your notebook might look:

I use the same system and process to prepare for all standardized exams. You can even use it to learn how to read EKGs better than a cardiologist.

With the Family Medicine Board Certification Exam around the corner, now is the perfect time to begin this system. It leaves time for adjustment and plenty of time to accumulate your unknown unknowns.

Strategy 2: Taking advantage of human error

Earlier in this post, I mentioned you’ll need two things to supercharge your standardized exam score: a notebook and time. The notebook you can buy anytime. However, time disappears.

Taking the time to identify your unknown unknowns will prepare you for the exam. However, we know five ways you can improve your score simply by showing up to your exam.

You can use the errors made by question writers to boost your score.

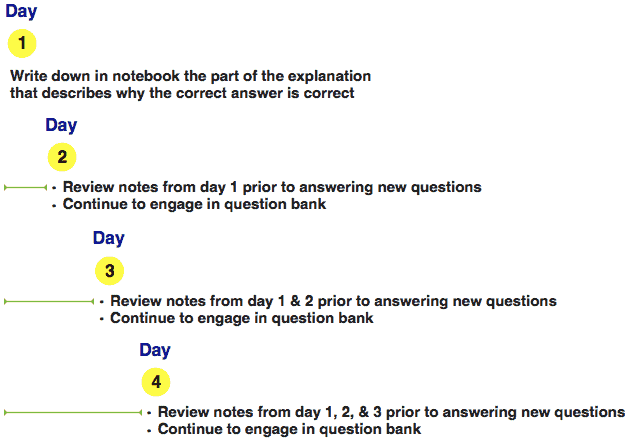

The Anatomy of a Question

First, let’s understand the anatomy of a question.

Question

A 67-year-old woman who was recently diagnosed with breast cancer presents with increasing confusion over the past three days. Additionally, over the past week she has been complaining of fatigue, diffuse body aches, poorly localized abdominal pain, and constipation. Which of the following electrolyte abnormalities is the most likely explanation for her symptoms?

A question is made up of the stem and the lead-in. The stem contains the details of the question such as the clinical presentation, past medical history, and laboratory results. But, the critical part of the question is the lead-in. The question writer uses the lead-in to find out what you know or don’t know about the topic in the stem, and it is also where question writers make errors. By applying basic grammatical analysis, you will be able to identify the correct answer or at least narrow down the answer choices without knowing anything about the topic. Here are our first two tips:

- Pay attention to grammatical cues:

Grammatical cues: one or more answer choices (distractors) don’t follow grammatically from the lead-in.

A 25-year-old woman presents to your clinic with concerns about sexually transmitted infections. She reports that she had unprotected intercourse with multiple partners. She is asymptomatic, but her last partner told her that he recently tested positive for chlamydia. The most appropriate next step is administration of which of the following?

A. Azithromycin

B. Obtaining a urine sample

C. Penicillin

D. Vaginal swabbing

B and D do not follow grammatically from the lead-in. A good test taker can eliminate these.

2. Focus on logical cues:

Logical cues: one or more answer choices don’t logically fit in with the other choices.

A 22-year-old man is concerned he has appendicitis. Which of the following signs is most sensitive for the diagnosis of appendicitis?

A. Nausea

B. Pain with extension of the hip joint

C. Rebound tenderness

D. Right lower quadrant tenderness

Nausea is not a “sign” and can be eliminated by a good test taker.

Let’s now focus on answer choices to identify a few more areas where we can gain an edge.

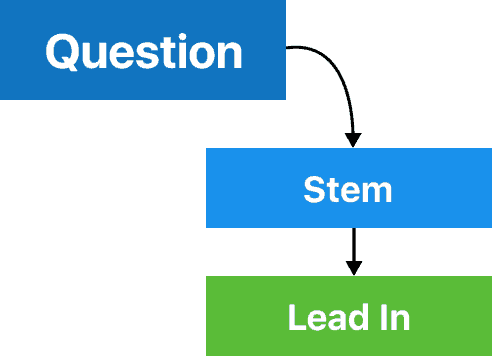

The Anatomy of Answer Choices

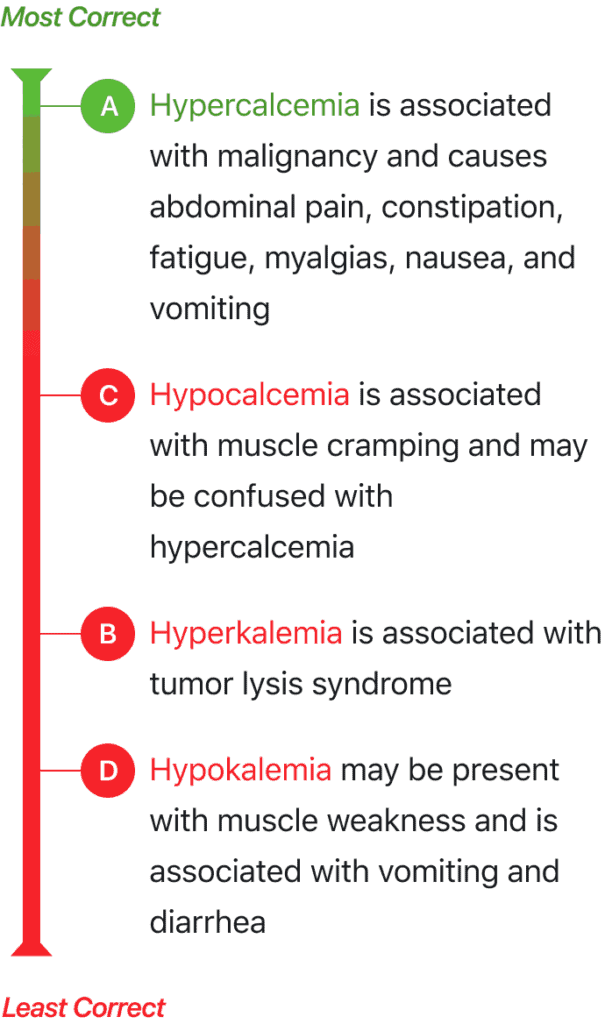

QUESTION: A 67-year-old woman who was recently diagnosed with breast cancer presents with increasing confusion over the past three days. Additionally, over the past week she has been complaining of fatigue, diffuse body aches, poorly localized abdominal pain, and constipation. Which of the following electrolyte abnormalities is the most likely explanation for her symptoms?

A. Hypercalcemia

B. Hyperkalemia

C. Hypocalcemia

D. Hypokalemia

The lead-in asks about the most likely explanation, so think carefully through each answer option. Here are the distractors:

Once you understand the goal of the question writer to create answer choices that are supposed to discriminate knowledge, it is easier to exploit technical flaws and improve the odds of getting a question correct. The following three pointers round out our five tips that can help you answer a question correctly:

3. Look for answer choices containing absolute terms.

Absolute terms: terms such as “always” or “never.” When used in the answer options, these terms usually indicate an incorrect answer because they cannot hold up to scrutiny in all situations.

In patients with advanced Alzheimer disease, which of the following best characterizes the memory defect?

A. Can be treated adequately with phosphatidylcholine

B. Could be a sequela of early parkinsonism

C. Is always severe

D. Is never seen in patients with neurofibrillary tangles at autopsy

C and D contain absolute terms “always” and “never.” These should be avoided in answer choices because they are less likely to be true statements.

4. Keep an eye out for a long correct answer.

Long correct answer: the correct answer is longer, more specific, or more complete than the other options.

Secondary gain is which of the following?

A. A complication of a variety of illnesses and tends to prolong many of them

B. A frequent problem in obsessive-compulsive disorder

C. Commonly seen in organic brain damage

D. Synonymous with malingering

Option A is longer than the other options, and it is also the only double option. Item writers tend to pay more attention to the correct answer than to the distractors and write long correct answers that include additional instructional material, parenthetical information, and caveats.

5. Notice when a word repeats.

Word repeats: a word or phrase is included in the stem and in the correct answer.

A 13-year-old obese boy presents with a progressive left-sided limp over the past three weeks. The patient states that he has pain in his knee. On exam, you elicit pain on internal rotation of the hip. Plain radiographs show a left hip joint abnormality “like ice cream slipping off a cone.” Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Greater trochanteric bursitis

B. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

C. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

D. Transient synovitis

This question uses the term “slipping” in the question stem, and “slipped capital femoral epiphysis” is the correct answer.

Whether you are taking your Family Medicine Certification Exam or ITE, there is so much at stake. Taking the time to identify your unknown unknowns will not only help you prepare for and excel on your exam, it will help you expand your core knowledge. Then, on test day, use the five simple techniques to identify common flaws in questions which will increase your chances of getting a question correct.

Give these methods a try and let me know how it goes. Moreover, I’d love to hear about techniques you use that I did not write about.

And if you are looking for a family medicine board review Qbank…you know where to find one.

Best,

Jennifer Conroy, MD

Get Free Access and Join Thousands of Happy Learners

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Comments (0)