Question 1 of 7

Internal Medicine

A 7-year-old boy is being seen for a well-child checkup by his primary provider. During routine screening, his parents report that he has several hour episodes of being “wild” about once per week. They are unable to identify any particular trigger. When asked to elaborate further, his parents report that he keeps acting up until he gets their attention and ends up in a time out. He throws his toys around, hits his older sisters, and swears at his mother. His father is worried that his son has bipolar disorder, as his paternal grandmother was institutionalized with “manic depression.” Review of systems is significant for sleeping only five hours each night and then being full of energy the next day. The boy’s mental status exam is significant for irritability, labile affect, oppositionality, and distractibility. The provider tells the parents that the boy does not meet criteria for bipolar disorder. Which of the following is the most likely rationale for the provider’s decision?

A Atypical sleep pattern

BDiagnosis excluded due to age

CInsufficient duration of episodes

D Irritable rather than manic mood

Explanation

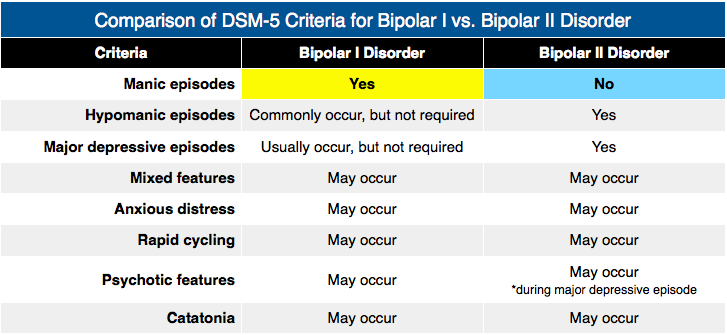

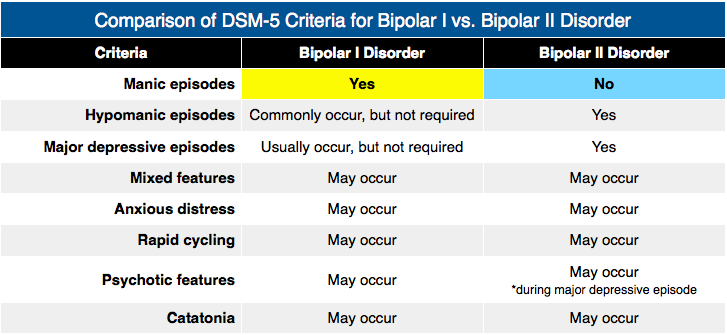

An insufficient duration of episodes excludes the diagnosis of both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder, as the DSM-5 requires that the distinct period of abnormal mood be present most of the day, nearly every day. For bipolar I disorder, the distinct period must last for at least one week, whereas for bipolar II disorder, this period must last for at least four consecutive days. The only exception to the total duration criteria for bipolar I disorder is that any duration meets criteria if hospitalization was necessary. In the vignette described, the following features exclude the diagnosis of bipolar disorder: several hour episodes occurring one day per week and not resulting in hospitalization (mood issue being brought to attention during a well-child checkup). For a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the DSM-5 further requires additional symptoms such as grandiosity, flight of ideas, and increase in goal-directed activity. Bipolar I disorder requires a history of at least one manic episode, whereas bipolar II disorder requires a history of at least one hypomanic episode and one major depressive episode. Criteria for a manic episode require accompanying marked impairment in functioning, hospitalization, or psychotic features, whereas criteria for a hypomanic episode require only an unequivocal change in functioning. The prevalence of bipolar I disorder is estimated to be less than 1%, there is an approximately equivalent lifetime prevalence between males and females, and the mean age of onset is 18 years of age. There is a significant lifetime risk of completed suicide in individuals with bipolar disorder, which is associated with a past history of suicide attempt and the percent of days spent depressed in the past year. Treatment depends on whether the current episode is characterized by mania, depression, or mixed features; the severity of impairment; the presence of psychotic features; past response to treatment; and other individual patient characteristics. Mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, and the cautious use of antidepressants may have differential roles to play on a case by case basis. Treatment involves both acute and maintenance phases due to the recurrent nature of bipolar disorder. Psychoeducation is important, various psychotherapeutic approaches may augment maintenance medication treatment for some cases, and comorbid physical and mental health disorders also require appropriate interventions.

Rather than an atypical sleep pattern (A), the boy’s sleep pattern is consistent with the bipolar criteria for a decreased need for sleep. His sleep may require attention since it is less than the usual requirement for his age (approximately 11 hours), and inadequate sleep can trigger mood episodes. Diagnosis excluded due to age (B) is incorrect as the DSM-5 does not specify an age requirement for bipolar disorders. However, there has been considerable debate regarding whether it is under- or overdiagnosed in preadolescent children, especially. Misdiagnosing a child with bipolar disorder inevitably leads to unnecessary exposure to medications with significant side effects as well as negatively affecting the child’s and family’s beliefs about prognosis. However, missing a diagnosis of bipolar disorder may result in exposure to medications that worsen the clinical picture (e.g., antidepressants for manic and mixed presentations characterized by an irritable mood) and additional morbidity due to the delay of effective treatments. Clinicians must strive to carefully consider diagnostic criteria along with other factors (e.g., family history, response to medications) in their diagnostic deliberations. In the vignette described, the boy’s affective instability and family history of bipolar disorder require ongoing vigilance for the possibility of bipolar disorder, even though he clearly does not meet criteria at this time. Instead, his presentation appears to reflect a behavioral disorder in his seeking of parental attention. Bipolar disorders may present with an irritable rather than manic mood (D). The DSM-5 specifically describes that the mood must be either “elevated, expansive, or irritable.” When the predominant mood is irritable, there is a requirement for four (rather than three) symptoms in addition to the abnormal mood state.